Following are just some thoughts I’ve been working with. They’re probably not very coherent, and they’re certainly not intended as the last word on anything.

First of all, I suppose some might wonder why I write “Celtic” in quotes. In the field of archaeology, there are those who believe that there was sufficient cultural unity among the Iron Age peoples who lived in the area between the Mediterranean region in the south, Scandinavia in the north, and the Scythians in the east to call them by a single cultural name, which is Celts. The name is ultimately derived from the Greek name Keltoi, but no one knows if they used such a name for themselves, and anyway Keltoi went out of vogue along with Greek hegemony. The Roman version of the word was Gaul, but they applied it more specifically (e.g., for the Romans, people from east of the Rhine were Germans, not Gauls–even though archaeologically they look the same as their neighbors west of the river). The name Celts came out of 19th-century linguistics, when languages were being categorized and placed onto phylogenetic trees; a linguist (can’t remember his name off the top of my head, sorry) grouped Irish, Welsh, Scottish, Cornish, and Breton together and called them “Celtic,” figuring they were representative of the languages spoken by that particular flavor of barbarian the Greeks called Keltoi. So anyway, the archaeologists in this camp argue that these Celtic-speaking people’s commonalities outweighed their local differences, and they would have all recognized one another as belonging to a semi-coherent group relative to outsider groups (Romans, Scythians, what have you), so we can safely call them all by one general name.

There is another camp who believe that, while there is evidence from placenames to suggest that languages belonging to the so-called Celtic branch of Indo-European were spoken within the region described, and a decorative style (La Tène) which became widespread (notwithstanding local variations) there, that is not sufficient evidence to conclude that everyone in temperate Europe would have identified with one another. And if they didn’t, then there’s no reason we should. For this group of scholars, use of the term Celts requires that they define the term anew every time they use it, with the literature review and the dozens of citations, the arguments for and against basing cultural ascriptions on language, etc., that inevitably would require–so it’s just not worth the effort. It’s much easier to use a more specific term like “the Late Pre-Roman Iron Age population of Lower-Humpton-on-Doodle” for example, since academic papers always tend to be focused on one narrow little time and place anyway.

I find the second argument more persuasive–and would apply it equally to other putative unified groups like Scythians and Germans and Native Americans–but I recognize that Celts has a certain meaning for most people today: that is, Celtic-speaking people living in temperate Europe from the Iron Age up through the early middle ages, who made La Tène- or medieval Irish-style art. In modern times, people from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland and their American descendants have found common cause in Celtic identity, which in part has enabled resistance to British (English) colonialism, and that shared identity has been retrojected into the past. That’s problematic, if understandable, and if I were writing for an academic journal I wouldn’t use the term Celtic at all; but I use it since it has meaning for people today, though I put it in quotes to show the word has issues.

Wow, that digression was rather longer than I intended. But in a way, it’s emblematic of the entire problem that has been bothering me, which is:

We need to stop trying to shoehorn the past into our modern categories. And we need to get more rigorous about our epistemology.

I’ll be honest. There’s a side of me that is really bothered by historical inaccuracy. There is another side of me that is aware of all the myriad problems with “history” and “accuracy” but just doesn’t want to go there right now. I know how to keep my historical-reactionary side in her place but she is right that this need to apply modern categories to the past, or for that matter human categories to the divine, and the inability to recognize why these categories are irrelevant, have led to a lot of BS in paganism. By BS I don’t just mean trivial historical inaccuracies; I mean a complete unmooring from context. In the first Rune Soup podcast, an interview with Peter Grey from Scarlet Imprint, Gordon opines that if the current magical renaissance can be said to have a unique form or trajectory, it is the restoration of context to magic. That stuck with me because I have talked before about the pitfalls of loss of context, but to sum up my view, we don’t need to worry so much about accurate replication of some ritual practice or magical tech, but rather why we are doing it, why it even exists in the first place. And this should be an ongoing dialogue with ourselves and our spiritually significant others.

It’s cool to see people working to restore context to magic; is that happening within paganism too? I honestly don’t know as I’m not really a pagan. And the main reason I’m not is because of this lack of context.

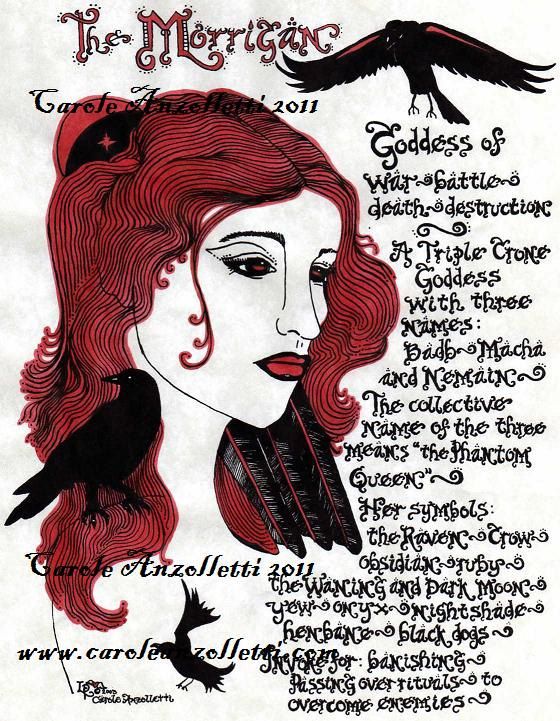

What specifically do I mean when I say lack of context? In my last post as I was singing the praises of the Story Archaeology podcast, I mentioned (not quite in so many words) that the hosts have basically demolished the notion that Mór Rígain (a.k.a., the Morrigan) was a war or death goddess. Yet this is the prevailing view of her in modern paganism even/especially among devotees of Irish deities. (See the Wikipedia article if you don’t believe me. It is terrible even by Wikipedia standards.) Now I’m not going to tell the Great Queen what she can and can’t do; perhaps she’s happy to be addressed as a war goddess. But we can only see her that way by essentially ignoring everything she does and says in the extant texts, and what kind of devotion or scholarship is that?

Is our psycho-cultural need to shoehorn Mór Rígain into a war goddess role so great that we are going to let it blind us (1) to everything else she actually is and (2) everything we could learn about ancient Irish/”Celtic” society/beliefs/values through a better understanding of her? And if our need is so great, what effect does that have on our personal gnosis of Mór Rígain?

This gets to my point about having a more rigorous approach to epistemology. On the one hand, we must learn to content ourselves with the fact that very little is known about the “Celtic” deities–in most cases we don’t even know who is a deity! This makes it all the more tempting to try and force a modern (usually Classically-inspired) framework onto them, to create a pantheon and categorize them according to what they are god/desses “of.”On the other, we really need to interrogate the assumptions and psycho-cultural needs we are bringing to the table and how they limit our experiences of these deities.

I think the case of “Elen of the Ways” is one of the most egregious examples of lack of context leading us into neopagan fantasyland. Like a lot of people with British ancestors, I’m a descendant of Elen Luyddog, or Elen “of the Hosts,” a Romano-British ancestrix saint to whom–or rather, to whose putative husband, the 4th-century Roman Emperor Magnus Maximus–many families trace their descent. We don’t know much about her from history, she could even be a historical fabrication or pure legend; much as I would like to claim descent from her as a goddess, it is a leap too far to ascribe divine status to her. Elen is also called “of the Ways,” because according to one medieval text, “Elen thought to make high roads from one stronghold to another across the Island of Britain. And the roads were made.”

This article is a thorough and concise explanation of this epistemological quagmire (if you like it, you should save it, because it’s already only available on the Wayback Machine). Elen appears in the tale The Dream of Macsen Wledig in the Mabinogion, in which Magnus Maximus (Macsen) is totally mythologized; there’s no reason to assume Elen didn’t get the same treatment. No one argues Magnus was a god, yet the magical elements of Elen’s part in the story are taken at face value:

“…which has led many modern pagans to proclaim her as a goddess of roads, ley lines, shamanic journeying etc….a goddess presiding over ‘dream pathways’ and the ‘Guardian of all who journey’….Some modern pagans see Elen Luyddog as a ‘goddess of sovereignty’…”

Oh boy. But wait, it gets better:

“…the modern pagan goddess Elen is often visualised or encountered as an antlered woman, often wearing deer hides or possessing fur herself. This image is as far from a cultured Romano-British Empress as is possible. Now, to take a sceptical view, this may be a chicken and egg situation. It happens that the Bulgarian word for reindeer is ‘elen’, and I wonder if someone has put two and two together and made five. To take a generous view, there is a remote possibility that Elen was originally a reindeer goddess whose name has miraculously survived into a modern language, and that she was the original ‘Elen of the Ways’ who later became conflated with Elen of the Hosts….For those looking for the oldest of the old religions, Elen becomes perfect. Not only does she appear to be a goddess of sovereignty, whom Macsen Wledig weds to gain the kingship of Britain, she also becomes a goddess of ancient pathways walked by a species of deer not seen in Britain since the end of the last ice age.

“This image of Elen, as far as I can gather, originates with Caroline Wise in the 1980’s…”

I think “someone has put two and two together and made five” sums this story up perfectly. Not only do we have the leap from politically powerful Romano-British woman to pre-Roman goddess of sovereignty, we also have the leap from commissioner of roads to primeval goddess of all forms of journeying. Now as far as that goes, it just seems to be a case of assuming every person in legend must be a god/dess and proceeding to inflate the case accordingly. A classic case of de-contextualization. But there is a weirder, more interesting, and potentially more problematic issue at stake:

“…it remains true that Someone out there, and possibly more than one Someone, is answering to the name ‘Elen’. This may be the ancestral spirit of Elen Luyddog, or it may be something else altogether….It is not unlikely that a goddess, perhaps because she likes the offerings being given, or because she is a powerful being in that particular locality, chooses to answer when a name is called. [It is not unlikely that a hungry ghost would answer, either.]…I have no problem believing that she could be a powerful ancestral being that has become attached to the roads that she has been associated with for at least eight hundred years, or that another entity interested in these roads has begun answering to the name of Elen.”

It’s that “another entity” that bothers me. We can never be completely certain, when we dial the Other side, who is going to pick up. To some extent that may even be a-feature-not-a-bug of the connection. But on a purely practical level, as a descendant of Elen, I want to know that when I call, it’s my 46th great-grandma who is answering and not some random stranger with no vested interest in my wellbeing. And if I reach out and touch someone who shows up as a reindeer goddess, I want to know who that being is–I don’t want to force a square peg into an Elen-shaped hole.

Improving signal strength and fidelity, however, is supposed to be part of what we are doing here, part of the whole point of magic. For those who are drawn to “Celtic” paganism, this all begs the question, do you want to know your deities (bearing in mind you’ll never have all the organizational details you would for Greek, Roman or Egyptian ones) or would you rather just play with Celtic deity paper dolls? And for all of us, what are we going to do to improve signal strength and fidelity? How are we going to improve our spiritual scholarship? How are we going to return context to what has been de-contextualized for 1000+ years? Are we really struggling down this old crooked path just to see our own psychodramas reflected back at us, or are we trying to do something greater here?

I’m not just “liking” this article because you shamelessly plug Story ARchaeology again! It is very clear, well-argued and points out some glaringly poor research and reasoning with regard to what “everybody knows” about “Celtic” “deities”!

LikeLike

Thank you! I will continue shamelessly plugging Story Archaeology at every opportunity. I’m quite simply amazed by the work you and Chris have done, in addition to which it is just damn good storytelling.

LikeLike

It’s a multi-faceted problem, for sure.

“Elen” called to me last year. I saw the image of the statue that was issued, and –to quote another possibly-fictive text, my heart “leapt up in joy.” The first time I invoked Elen to open the ways, immediately I saw the gates open up and the internal paths become sharper and clearer. Who-Whatever is behind “Elen” does function as a gate-opener and way-shower quite well.

I don’t dismiss the work of Caroline Wise, Chesca Potter, Elen Sentier, or even Andrew Collins (whom I have met, and who really is brilliant). These are people who lived and walked and Crafted on that land for decades with dedication. I’m not going to tell them that they’re New Age crap-a-doodles. Caroline Wise, in her book, admits that all the threads and connections that she and others have spun about Elen are quite gossamer, indeed. She doesn’t present it as established fact or established history. She presents it as a vision quest, a conundrum, a Mystery.

And she actually doesn’t present Elen as a Celtic Goddess so much as an ancient and unnamed Goddess-spirit of the Land, connected with the old reindeer tracks, of whom your ancestress is a manifestation, along with St. Helen, and along with a number of other figures both mythological and actual (and in-between).

But I digress. We don’t know how Godforms generate. We know they do. Both of the traditions I initiated into work with the “Welsh Celtic Deities” of the Mabinogion. I have no doubt that Cerridwen chases up through our initiatory path! But really, was Cerridwen historically worked with as a Goddess? We have a handful of references to Her as a source of bardic inspiration, along with a couple of associated names. Was Bran ever invoked? Arianrhod? Llew? I mean worked with, served, sacrificed to, etc.

I don’t know. I don’t think we’ll ever know unless some of the untranslated manuscripts languishing in European libraries find someone who has the time, money, and skill to translate them. But honestly, I actually doubt these Names were treated as Gods. We don’t know so much. We don’t know what Names came over with the various invasions of “Celts.” We don’t know what Names and Powers were already honored in the land by the time the Celts came. And DNA studies are blurring those timelines as well.

I think the good question is, “Why?” Why does a Power choose to come through here and now as an Elen figure? Why are modern Pagans so hung up on Mor Rigain as a war and death goddess? Assuming Mor Rigain has some agency in this, can we ask why She is choosing to emphasize this aspect of Her?

LikeLike

I love everything you have said here. The mystery of why these powers come through as they do, why they respond to one name and not another, even–or especially–when history suggests that they probably didn’t respond to that name before, why people have genuine experiences of these powers even though they perhaps “shouldn’t”, why one person’s gnosis is not the same as another’s…this is becoming one of the defining questions of my thinking. The only thing I feel confident of is that I have no idea what these powers really are or how/why they work. I don’t poo-poo the fact that they DO work, but that just makes it all the more confusing.

Of course I’m in no position to dictate to Elen or whomever about how they can and should manifest or what appeals they may respond to. (And I am really trying hard to avoid sounding as if I am trying to convince anyone to regard them in one way or another, because I have been told I have a tendency to come across that way when I don’t pay careful attention to how I express myself. All too often I get excited about a topic and get louder, and less careful, about my expression and, well, the train can go off the tracks.) But I feel like too often we say, “this works” and don’t ask what the implications are. As you say, the question is “why”? I don’t need, or even want, a Unified Theory of Magic; but you have to admit there are some potentially disturbing ramifications to the idea that if you call, *something* answers and that’s good enough.

And that’s especially true, I think, when worship is involved. I don’t worship any deity and though I’m a polytheist I don’t think of myself as a *religious* or *devotional* polytheist so in a sense I don’t have a dog in this race. Yet there’s a side of me that could become a religious zealot if I allowed it, so I am continually drawn to questions of religion and theology, but I also have to intellectualize them. Maybe, ultimately, we just can never know who is on the Other end of the line, and that’s where faith (or dogma?) comes in. The strength of a non-scriptural religion is that it can change with the times, but it’s weakness is that you’re always dealing with a lack of information, and more importantly context. I think the question of why (for example) Mor Rigain might be ok with being re-conceptualized as a Warrior Princess Death Battle Goddess becomes far more interesting in the context of the history that shows she likely wasn’t always that. I mean, what does that say about these beings? Do they respond to any attention? Is there a way we could talk about them that would piss them off or cause them to ignore us? Does Isis have an opinion on ISIS? Do they guide these re-conceptualizations in any way? Do we create god/desses? Do they create us? Is it all just consciousness soup?

Equally important are the questions we have to ask about ourselves, e.g., why do we have so much invested in Mor Rigain as a death and war goddess? I mean I can’t help but think that has something to do with the kind of immature warrior-princess fantasy “feminism” I was into when I was a teenager and which, to judge from pop culture, is very much a part of the current Western symbol set. What would it take for us to recognize, let alone embrace, a different Mor Rigain? At what point do our “Celtic” traditions deviate so far from their roots that they are just a fantasy of Celticness? Do we care? For my part, in my youth when I first started getting interested in “Celtic” polytheism, I was really into the idea but I just had this nagging feeling that these supposed deities were like cardboard cutouts. It’s not to say that everything I read about them was wrong, necessarily, but it certainly felt like half-truths at best. Ultimately I got so frustrated that I turned my attention elsewhere. Now as I’m becoming more acquainted with the textual context, I certainly don’t want to become stuck in some kind of textual fundamentalism, but all kinds of pennies are dropping into place; it’s just my UPG of course, but I feel like I am starting to see the “real” powers behind the masks. To me it feels like these were genuinely missing pieces, that no matter how much UPG people had of Mor Rigain as death and war goddess, that picture was so incomplete as to be useless to me. And now I can fit some of these pieces into the puzzle and it just feels more right.

I mean no matter how deep I dig I only find more questions. It’s turtles all the way down.

LikeLike