Pssst. This is actually Part I of my review of Gordon White’s Star.Ships. (Don’t worry, no spoilers.) It was starting to look like my review would be very long, so I decided to break this part out. Anyway, it’s not technically a review per se. What follows is:

- One archaeologist’s quickie review/opinions of archaeological theory and practice. It’s longish, but not technical.

- A former insider’s view, but not an exhaustive one. I speak here in terms of general trends within Anglo-American archaeology. (For historical and economic reasons, English is the hegemonic language-of-record for archaeology, but there are regional differences that I’m not fully versed in.)

- Possibly of interest as background/context for those reading Star.Ships. I am still reading it, but I find that it frequently motivates me to reflect on changes in archaeological theory, and how we got to where we are now, in terms of what we think we know, what information is canonical, and what is “anomalous”. I find myself thinking of what a non-materialist archaeology might look like, for example. The point of the book is to correct misapprehensions about the past which are there in part due to the fossilization of academic thought; my point with this summary is to give a former insider’s view of how the current (mis)apprehensions developed.

Act I

In the beginning there were antiquarians. They read a lot of (Classical) history and collected artifacts–and usually lots of pretty rocks, fossils, bird eggs, two-headed fetal pigs, and other curiosities of natural history.

There were some pretty remarkable ruins still visible on the landscape. Some of them, like Hadrian’s Wall, were known from historical records. Others, like Stonehenge, were mysteries and warranted further investigation.

Generally speaking, explanations came from either Roman texts or the Bible. If a ruin was big, and it wasn’t Roman, then almost by necessity it had to have been built by lost tribes of Israel or one of Noah’s sons.

At the same time, European countries were vigorously imperial, which was bringing Europeans into contact with very different cultures and people who looked very different. Racism was born, and so were the first stirrings that would one day become anthropology.

Act II

Antiquarians started to notice that artifacts and ruins didn’t necessarily match the received wisdom or historical texts about the past. There were civilizations where there shouldn’t be (i.e., where brown people lived), for example. Some started being more methodical when digging holes looking for artifacts.

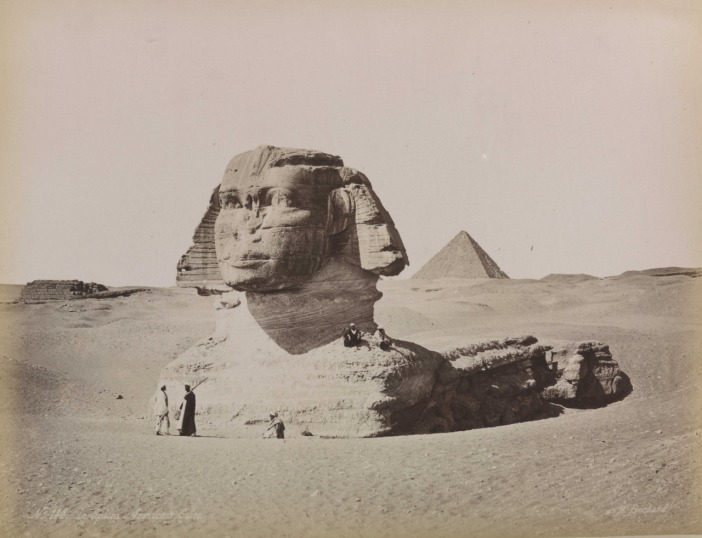

Romanticism was all the rage. Wealthy young men went to the Mediterranean for a “Grand Tour” to sigh over the crumbling splendors of civilizations past, and stole the nicer bits for souvenirs.

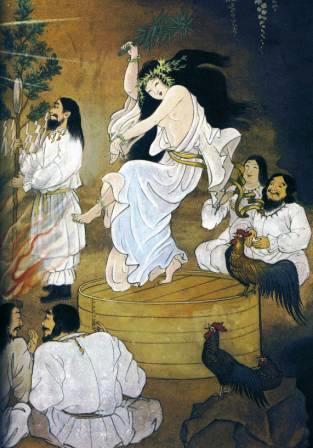

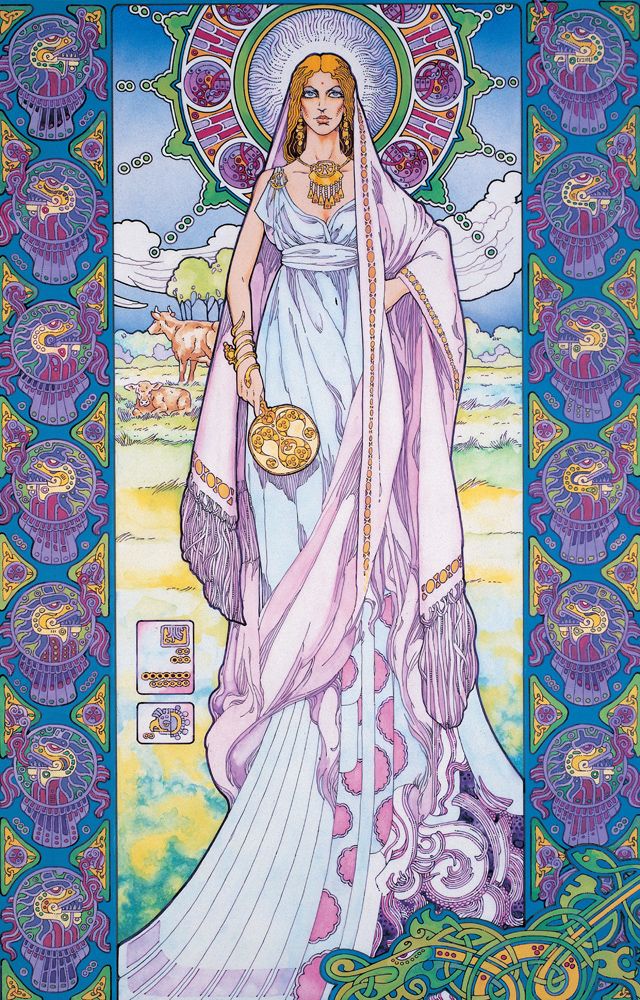

A number of well-known antiquarians were Freemasons, then Druid revivalists, and instead of lost tribes of Israel, they credited the Druids with anomalous ancient ruins. There was an element of nationalism here–now, finally, Britain and France could lay claim to an indigenous civilization that, while obviously not as grand as Rome, was still pretty cool, and perhaps in possession of Lost Wisdom.

Act III

The scientific method was all the rage. If you were independently wealthy you could round up some young peasants and go destroy some poor farmer’s field looking for booty artifacts. The better digs actually employed painters to make illustrations of remains in situ.

Archaeology, geology, historical linguistics, and palaeontology diverged as separate fields of inquiry. (In the Anglophone world, especially in the US, archaeology aligned with anthropology, the study of all things human.) Now instead of just keeping your finds in cabinets in your house, though, you donated them to museums for the public betterment. Scholars were busy classifying everything into typologies: eras, cultures, language groups, and so on. They particularly liked tripartite schemes, such as Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age, or Lower, Middle, and Upper Palaeolithic.

It was clear from all the artifacts and ruins that had been found that there had been great changes over time, only a small portion of which was recorded by history. This correlated with the evidence for gradual change found by the geologists and palaeontologists, and even–galling though it was for some–with the theory of natural selection as posited by Charles Darwin. The Bible began to look not so credible as an explanatory framework.

Observed cultural changes were usually put down to migrations. After all, historical accounts were full of invading Gauls, Huns, Goths, Vandals, Mongols, Angles and Saxons, you name it. Also, as imperialism and global trade put Europeans almost everywhere on earth, I imagine the idea of migration and invasion as catalysts for change seemed rather natural.

In a reaction against the racism and ethnocentrism of previous eras, Lewis Henry Morgan (1818-1881) proposed the “stage” theory of human cultural development: all societies, left to their own devices, passed through stages of Savagery, Barbarism, and Civilization. This was a corrective insofar as it reminded the imperial powers they once were savages too, and tried to make them feel a little guilty for derailing the civilizational processes of the assorted brown-skinned societies whose heads they were busily measuring with calipers in between all the murdering and enslaving.

Act IV

Things continued apace until the era of the World Wars (WWII in particular). By midcentury, the Bible was right out and Science-with-a-capital-S was in. Science had just given the world chemical fertilizers, nerve gas, and the A-bomb so obviously was the pinnacle of human achievement. Archaeologists could rely on radiocarbon for precision dating, even.

In true scientistic fashion, archaeology became about finding out “what really happened”. It was still entirely historical in the sense that it was about establishing chronological sequences, but it was anthropological insofar as it looked for evidence of how humans interacted with each other and with their environment. There was also increasing interest in what ordinary people did (e.g., as revealed through trash piles) rather than grand narratives about the great and the good.

V. Gordon Childe (1892-1957) was a Marxist and materialist who was very instrumental in formalizing archaeology’s nascent material bent. He mostly rejected the three-part stage theory developed by Morgan, but, being a Marxist, he did very much believe in the notion of cultural evolution. His big contributions were (1) to systematize, in explicitly material terms, the characteristics of categories such as “civilization” or “Neolithic”–in other words, he defined what these terms would mean as archaeological categories. And to a great extent, his criteria are still being used, because they are now efficient and convenient. (2) He attributed cultural change to purely material causes. And (3) while not rejecting migrations entirely, he argued for change due to other factors. I can’t help but think this was in part a reaction to the fact that a number of countries in Europe and Asia had literally just been invaded, and were feeling the sting. Also, the Nazis had revealed the dark underbelly of archaeology and anthropology.

Chief among these “other factors” was diffusion, which is basically just a fancy word meaning that objects and ideas can move without migrations, e.g., through trade. If you live in the West and own a Korean smart phone, that’s an example of diffusion. However, while it’s not technically part of the definition of diffusion, an underlying assumption was often that objects and ideas go from “more advanced” to “less advanced” cultures.

“Historical particularism” was very popular as a theoretical framework, basically rejecting the idea of human universals and attributing cultures’ specific features to their specific environments, prior histories, and internal dynamics. “Cultural-historical” archaeology has probably had more longevity, worldwide, than any other mode. It is constantly mobilized in the creation of both national identities and nationalistic propaganda. I would say it is the most popular form of archaeology for the general public, too, who mostly what to know “what really happened” for a given time and place. Chronology and treasure are the bedrock of archaeology.

Act V

In the US (which is what I’m familiar with), the 1960s saw the rise of hard-core scientism with the “New Archaeology” a.k.a., “processual” archaeology. (Processual because it focused on processes, you see.) Archaeologists were desperate to make it clear to all and sundry that archaeology was a (social) science, dammit, not humanities! When I say science I mean physics. It’s pretty absurd–nothing humans do is similar to what, say, atoms do; but it was the Atomic Age, after all. It was also the Cold War. No one knew what the hell was going on archaeologically in Russia or China, except that it was undoubtedly bad, and Marxism was very out of fashion as a theoretical framework. (It continues to flourish in Japan, and of course in China.) New Archaeologists desperately wanted universal rules that would explain human behavior, and if a proposed mechanism wasn’t general it was regarded as irrelevant.

On the positive side, American archaeologists developed extremely methodical and precise excavation technique which is, in my opinion, unequaled in other countries. They also developed the concept of “interaction spheres”, where it was observed that, in contrast to the assumption that ideas and objects diffused from “center” to “periphery”, interaction forms complex webs and things move in all directions. On the negative, the theoretical became incredibly mechanistic, materialistic, and and deterministic. Consensus opinion swung even harder away from migration as an explanation for change, and the attempts to put everything down to independent invention got silly.

Act VI

Beginning in the late ’80s we had “post-processual” archaeology, which was a straight-up reaction to the excesses of the now-not-so-new New Archaeology. Things got very postmodern, but also very philosophical, and therein lay the big contribution of this period. French philosophers like Foucault, Latour, Merleau-Ponty, and Bourdieu were wildly popular. Archaeologists (and anthropologists) really began to question the epistemology of anthropology and of academia in general. Instead of just asking, “How do we know these people did X?” they started asking “How do we know anything at all?” Unfortunately, they did so with the worst kind of jargon you have ever seen. Anthropological texts became completely opaque, difficult even for insiders to understand. The attitude seemed to be that if it was clear, it was not worth publication (let alone a tenured professorship).

Popular topics of inquiry were “habitus” (borrowed from Bourdieu) and “agency”. Some archaeologists even considered whether artifacts have their own agency, although not, sadly, in the animistic sense. Instead of looking at cultures as collections of mechanistic “processes”, archaeologists became increasingly focused on the individual. Which is interesting, and a bit futile, since individuals’ concerns and acts are rarely visible in the archaeological record. Interpretation was focused on the hyper-local, in contrast to the universalism of the previous period; and interpretations were explicitly identified/confessed as such.

Archaeology remained “methodologically atheist” and materialist, but more attention was paid to people’s experiences, perceptions, and feelings. The processual archaeologists and the cultural historians laughed and laughed.

Act VII

You will have noticed that during the 20th century, theoretical fashions started changing much more quickly in archaeology. Well, of course that parallels the rapidly changing fashions everywhere else. We seem to have settled into a series of reactionary swings of a roughly 20-year pendulum. Each new generation rejects the models of the previous one, but because the shifts are so rapid, the supporters of the previous theoretical framework are still around to heckle the young upstarts.

We are currently (since the ’00s) in a very scientistic mood, where more archaeology is done in labs than in the field. About the only kind of research that can get funding is research that involves some kind of physics or chemistry–isotopic analysis, X-ray fluorescence, genetics, microprobe assays, 3D scanning and printing, etc. There’s nothing wrong with these techniques, and they have revealed new kinds of information we couldn’t get at before. For one thing, isotopic and genetic analyses have put migration back on the table in a big way. Cultural changes (such as the Bell Beaker phenomenon) that were first put down to migrations, then to competitive elite status displays across interaction spheres, are now turning out to have actually been related to migrations. Mathematical shape analyses of bones have revealed evolutionary differences that we previously had to pretend didn’t exist because they couldn’t be quantified.

Unfortunately, the theoretical, anthropological questions that used to motivate such analyses are getting to be scarcer than hen’s teeth. I feel that the current moment in archaeology has borrowed the worst traits of the two previous eras: the super-scientistic, materialistic bent of processual archaeology that naturalizes and legitimizes certain interpretations of the data; and the hyper-locality of the post-processual era that is so laser focused as to be virtually irrelevant to anyone who is not a specialist in the time, place, and individuals under investigation.

In our current anti-intellectual climate, ain’t nobody gonna get no funding for a project that ultimately seeks to investigate what it means to be a human, and what the human experience has been through time. Funding agencies want sexy results that will make the New York Times and National Geographic and in turn bring in even more money. This usually means either discovery of treasure (rich tombs with lots of gold, King Tut-style); something that claims to turn everything you ever knew about X upside-down (ancient Caucasian-looking mummies found in China); or discovery of a new civilization or fossil human ancestor (the latter isn’t even archaeology). You would think that would at least make for some exciting, Indiana Jones-style research, but that’s not the stuff that makes for tenured professorships: When I was briefly on the academic job market (before my mom getting sick saved me), it seemed like all the job listings were for people who would do some kind of lab-based sciency analysis of pottery and work in the Eastern Mediterranean. Yawn. (Even so there are too many applicants for those positions.) Meanwhile the journals were full of strontium and oxygen isotope analyses of this or that cemetery which noted that X% of the people interred were migrants from Wherever, but never bothered to tell us why we would give a shit and why it was worth grinding up some irreplaceable ancient teeth and spending tens of thousands of dollars to find that out. In the worst cases it’s just fill-in-the-blanks culture-history.

In conclusion

If you’ve read this far, it’s probably pretty obvious (if it wasn’t already) how and why archaeologists end up painting themselves into interpretive corners. To use Gordon’s analogy, it’s like a game of Jenga where, if you pull just one little log out, the entire edifice comes crashing down. And ultimately, it wouldn’t just be the edifice of archaeology, or even anthropology. All of academia could come down with it.