This post has been sitting in my drafts folder for a while as I wasn’t sure quite where to take it. But Ivy at Circle Thrice just posted about narratives and it got me thinking about this again, so I decided this might be worth publishing after all.

Ivy refers to Walter Fisher’s Narrative Paradigm theory, which basically says that people don’t make decisions or experience the world in terms of a rationalist evaluation of facts, but rather “The ways in which people explain and/or justify their behavior, whether past or future, has more to do with telling a credible story than it does with producing evidence or constructing a logical argument” (my emphasis; source). And of course “credibility” is in the eye of the beholder, so it’s subjective and subject to constant negotiation not only among individuals but within the individual as their idea of the credible inevitably changes.

The story is what we care about, not the facts. The story is the framework that gives, and relays, meaning and value. But in our creative Homo sapiens hands, it’s shifty, slippery, tricksy; as beautiful as it is dangerous.

If you read my post about my tentative ontology, you might be seeing where this is headed. But let me unpack it a bit.

I’m assuming you have seen the movie Rashomon, and while I won’t spoil the plot points, I will be talking about its philosophical take-away, so if you haven’t watched it, go do that now.

In the so-called “Rashomon effect,” different witnesses to or participants in a given event remember it differently. I’m sure we’ve all experienced the truth of that; memory is notoriously malleable and fallible after all. I have often heard this effect described as the entire point of the film (or rather, the short story on which most of it is based, In a Grove by Akutagawa Ryunosuke)–that is, that the moral of the story is that memory is fallible and people have different perspectives. But that is the most superficial meaning that can be derived from the story. I mean–witch, please–this is Kurosawa we’re talking about.

The more fundamental point of the story is that individuals can become so committed to their personal storylines that they would sooner kill, die, even endure hell than imagine themselves not to be the heroes of those stories. At the end of the film, the truth of the events upon which the plot hangs not only isn’t revealed, it is revealed to be unknowable. No two characters give the same account of events because no two characters are living out the same storyline. Rashomon isn’t a whodunnit, it’s not just stating the obvious fact that people remember and interpret things differently–it’s a meditation on maya and suffering.

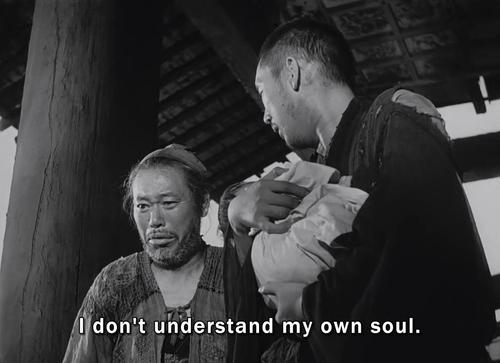

To make that even clearer, Kurosawa brilliantly set the story of In a Grove within another Akutagawa story (the one actually titled Rashomon). This frames the more dramatic, acute suffering of the events in the grove within a setting of more ordinary, chronic suffering–the stifling heat and humidity of a summer monsoon, poverty, and a haunted gatehouse ruined by war and natural disaster. Here a witness to the events in the grove, a Buddhist monk, and an ethically-dubious passerby consider the plight of an abandoned baby and debate human nature and the human tendency to lie, even to ourselves as is repeatedly noted. “I don’t even understand my own heart/mind/soul*,” says the witness. The redemption offered at the end of the movie is not the discovery of the truth about the events in the grove (as it would be if the movie had been made in America), but rather the observation that when we finally admit our own lack of understanding and let go of our death-grip on our personal narratives, we become more compassionate and suffer a little bit less.

You can approach the story at various levels. First, staying entirely within the world of In a Grove, you have the the basic level of human experience. At this level, the protagonists cannot face the possibility that they are venal, weak, and morally-challenged, so each rewrites the story to portray him- or herself in a better light. Lies are told (maybe, probably), memories flawed and finagled. It’s almost an organic process rather than a series of conscious decisions. Subjective truth is all, and objective truth doesn’t even enter into it.

Pulling back to a slightly wider scale, the scale of Rashomon-the-story-within-Rashomon-the-film, the characters are aware of the fallibility of memory, of the human tendency to deceive ourselves and others and to be deceived, and must acknowledge that objective truth is inaccessible.

At the next level, we can look at the authorial choices of Kurosawa as the director. By framing In a Grove within Rashomon, for example, he created space for reflection within the film. He also used the environment masterfully: The blazing sun in the In a Grove core contrasts with the torrential downpour in the Rashomon frame, while both are united by the characters’ ever-present sweat. (One time when I was in Korea during the monsoon season it was like 85 degrees and foggy. It’s like being in a sauna but with bugs and you have to wear clothes.) The scenes shot in the forest are disorienting, filled with broken patterns of leaves and light and blurred motion. There are only three sets–the gatehouse where the witness, monk, and passerby wait out the rain, the forest, and a courtyard where witnesses testify before an unseen magistrate. On the Criterion Collection DVD there is an introduction by Robert Altman who points out that the testimony scenes are shot with the characters speaking to the camera, so the audience is placed in the position of the magistrate or investigator. It’s as if Kurosawa is daring us to arbitrate or “solve” the mystery–which cannot be solved, so… It all combines to build a subtle but palpable sense of oppression, claustrophobia, and confusion.

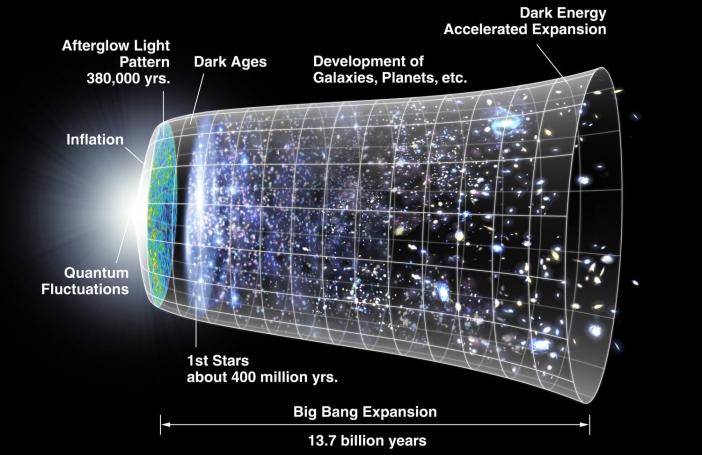

We can pull back further (so meta!) and examine ourselves as the audience, considering Kurosawa’s direction and storytelling and how the medium of film makes it possible to tell these stories within a story within a story. We can try to take up the challenge to determine the objective truth of what happened in the grove (though that would be an exercise in futility) or we could settle for the easy way out and say the story is about people’s different perspectives. Or we can do the hard work and recognize we are looking at stories within a story within a story within our story (and so on and on and on, fractally) and think about how our own stories nest into wider and wider ones. And also, what it means to recognize and own them as stories.

Rashomon‘s are very Buddhist values, of course, but we are talking about a Japanese story/film. In writing about the power of narrative, Ivy points out some of the ways it can be weaponized against us (it is part of her Mind War series). Hijacking a narrative is the easiest and fastest way to manipulate people’s actions and beliefs, because you are effectively hijacking their entire reality. So it stands to reason that if you can (1) recognize your narrative as just one among a nearly infinite number; (2) recognize that you are a character in other people’s narratives, but your roles are not something you can experience, let alone control; and (3) reduce your investment in your narrative’s truthiness, you will have made yourself much harder to deceive or manipulate. And perhaps more importantly, it will be harder to deceive yourself.

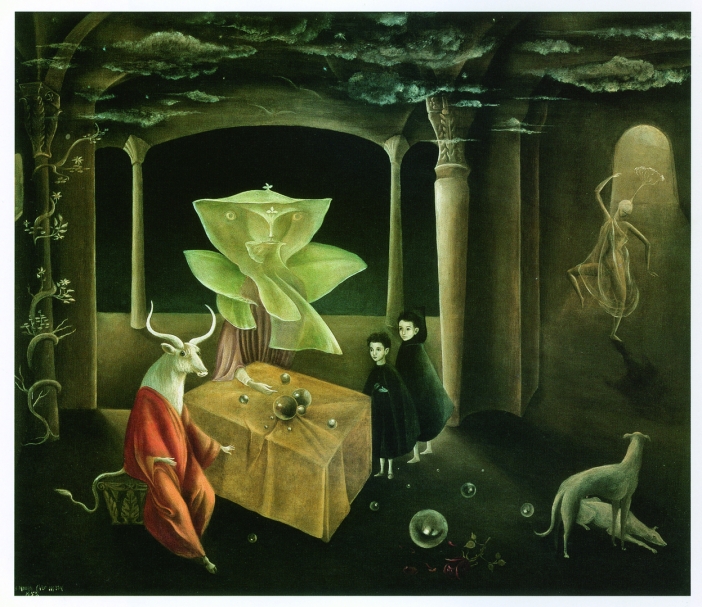

When you put Rashomon‘s internally-focused narratology together with Ivy’s externally-focused one, it becomes clear how you can re-frame your narrative–and thus your reality–in astoundingly creative ways; i.e., magic. No, I don’t mean that magic is all psychological. I mean that when you recognize the narrative and take the reins, you can rewrite the entire meaning of your life. It’s one way to hack the code of your virtual reality, or to use my preferred metaphor, start dreaming lucidly.

But you have to be prepared for everything to fall apart, as it will. The Western world is extremely invested not only in the belief that objective truth exists, but that it is knowable and discoverable given the right techniques. One place you see this reflected is science, of course, another is the Bible, but it’s reified everywhere in our epistemologies. Reason and philosophical rationalism are highly esteemed here not only as intellectual projects but as personality characteristics. When you recognize your story as more creative writing than truth, shit goes upside down and you have the fun of sifting through and reevaluating (or sort of de-evaluating) everything you’ve taken for granted in your past and present. Undertaking this will put you (even more) profoundly out of step with most of the people around you and will definitely make you question your sanity on a daily basis.

On a personal note, my helping spirits have recently doubled down on the assignments they’ve been giving me. I have to keep a journal just to remember all of them. And guys. It’s all in aid of something I want and something I asked for, but the work is so hard sometimes. Recently I got slammed with a whole series of synchronicities that, while fun at the time, led me down a very dark rabbit hole. I have been encouraged to not only ignore but explicitly reject the evidence of my senses and the public written record (faith doesn’t come easy to me), while also dealing with some decades-old emotional junk. I wouldn’t have been given this task if I weren’t up to it, and the spirits are taking me through it step by step, but that doesn’t mean I can’t fail (as I have before), and it’s definitely pushing my limits.

When I put it in words it doesn’t look like that big a deal, especially since I’ve been rejecting consensus narratives since I was little (like you, I expect), but this time I’m working not just on rejecting external narratives but internal, heavily-invested ones as well. Working on this is taking most of my mind/heart resources which is why I haven’t posted as much lately.

*Kokoro, which doesn’t really translate in English but corresponds to our notions of “heart” and “mind,” and to some extent “soul” (though there is another Japanese word, tama, which better fits “soul”).