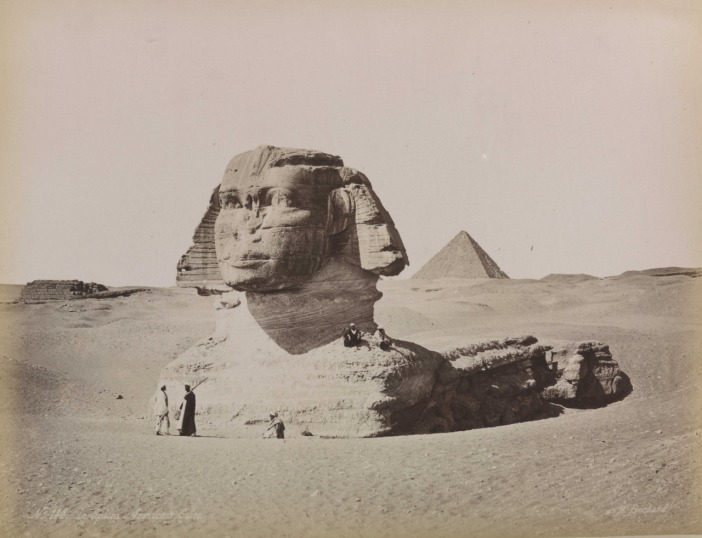

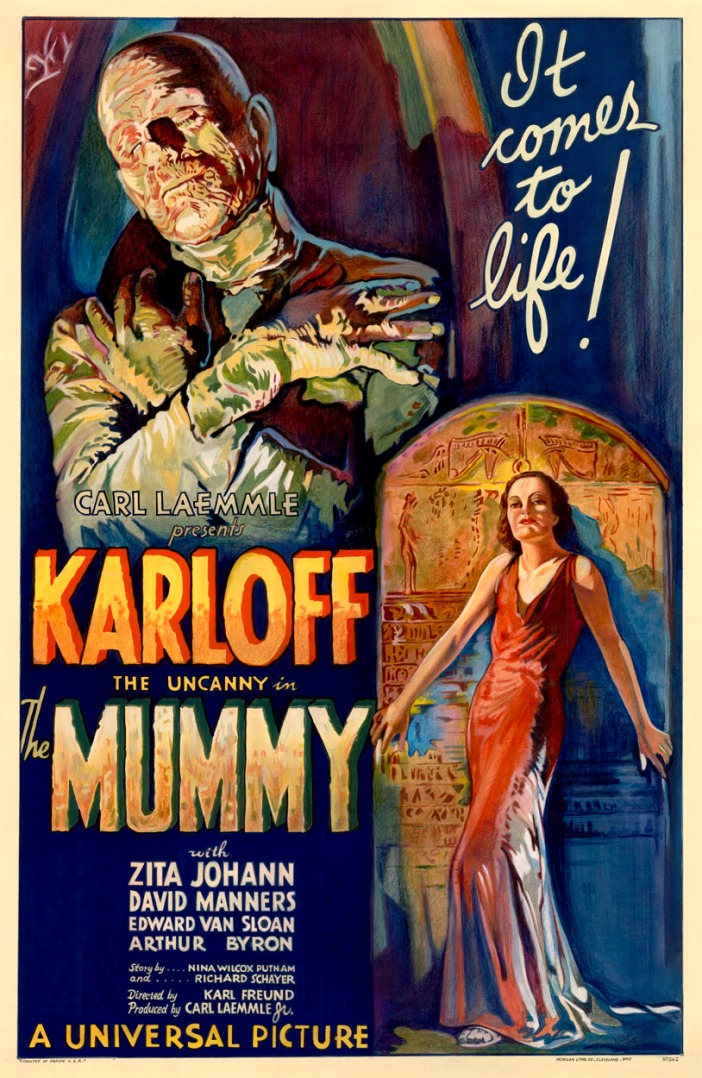

Last night I saw the latest iteration of Universal’s Mummy movies, and boy was it terrible. I knew it would be bad, but there is no air conditioning in my current digs, it’s hot and humid, the movie theater only charges $5, and I had already seen every other film there that I could even remotely stomach. I am a huge fan of classic* monster movies, and the Mummy is my favorite monster. How could it be otherwise for an archaeologist? Many moons ago I wrote a (rather well-received, if I say so myself) paper for an archaeology class, comparing The Mummy (1932) with The Mummy (1999), so I figured I could handle The Mummy (2017) in the name of ongoing scholarly research.

Spoilers below.

But honestly there is no way to spoil a movie this bad.

First some general ruminations: Right out of the gate, this version of The Mummy was bound to suck because it’s been given the Tom Cruise/summer blockbuster/comic book treatment. Apparently Universal is launching a monster franchise a la the Marvel and DC Comics franchises, called Dark Universe, where all the monsters will be shoehorned and (monster-)mashed together. There are winky nods to the 1999 film that are utterly contrived and cringeworthy, as if to prove that hey folks, this is a coherent universe just like Marvel! This seems ill-advised to me in that, as far as I know, monster and comic book fandoms don’t really overlap much. I could be wrong. Anyway, I never liked the “Dracula Meets Frankenstein” type monster movies, nor do I like superhero movies that involve more than one superhero. I don’t know…I guess I can suspend disbelief in one superhero, or even an entire race of immortals like in The Highlander (please please please please please no Highlander reboots, Hollywood, I am begging you), but a whole posse of superheroes raises ontological questions for me that are never satisfyingly addressed.

In theory I could more easily embrace the idea of a multi-monster cinematic universe, because the supernatural comes in many flavors, but the more monsters you add, and the more types of monsters, the more you dilute their impact. Especially with the classic monsters (Dracula, Frankenstein, the Mummy, the Wolf-Man, Phantom of the Opera, even King Kong and the Creature from the Black Lagoon), there is a distinctly erotic component that works because it taps into semi-conscious desires and fears. In a sense the monster is the masculine id unleashed. The horror is in the individual’s subjective encounter with the Weird, which as we know from real life, is always unique and unrepeatable.

But that can be a topic for another day.

Returning to this specific iteration of The Mummy, I’m more concerned about the disturbing subtext. So let me rant about that for a bit.

The “hero”

As you would expect from a Tom Cruise movie, it is more about his character, Nick Morton, than about the titular mummy. The Mummy feels like a McGuffin provided solely to universe-build for a new superhero. But Morton is a truly vile excuse for a human being: a US soldier who uses reconnaissance duty as a cover to loot Middle Eastern antiquities to sell on the black market. This lifestyle is referred to in the film as “adventure.” Now I love a good Film Noir-style antihero; and Hollywood’s take on adventure has always played pretty fast and loose with laws and ethics. Usually they manage to create protagonists who walk the fine line of roguish-but-likeable or outlaw-for-a-good-cause. For example, Brendan Fraser’s character in the 1999 version of The Mummy: it’s implied he is a mercenary and treasure hunter but he’s never actually shown looting anything, whereas those who explicitly loot all meet grisly ends. But Morton goes beyond antihero straight into Horrible Person territory, and it’s all the more unsettling given the dubious reasons for US interventions in the Middle East in the first place. Morton is about adventurism, not adventure. We’re supposed to believe Morton is actually a good guy because he saves a woman’s life, but sorry, I think the scales of Ma’at are far from balanced and I find it really disturbing that the film’s creators apparently think this level of bad-person-ness is something that can be cheerfully overlooked. The subtextual messages here are:

(1) If you’re an American (especially a soldier) you can pillage other nations’ cultural heritage and that’s ok, not only will you get away with it, it’s really just entrepreneurial spirit and “adventure.” Sure, as with archaeology there’s always the risk of unearthing unspeakable ancient evils, but they’re no match for GI Joe!

(2) The other day I was joking with a friend about what the Lord of the Rings would have been like if Tolkien were American. Among other things I speculated that Frodo and Sam would be cops. It’s no accident that our “hero” is a soldier, because apparently it’s no longer possible for Americans to conceive of a hero who is not military or paramilitary personnel. Note that in the original 1932 Mummy, the heroes were archaeologists. Nerds. And I mean actual boring archaeologists, not Hollywood’s idea of archaeologists, which is just looters with Ph.D.s.

Speaking of archaeologists, in the new movie it’s implied the female lead, Dr. Jennifer Halsey, is one, but actually she’s a monster hunter. There’s no need for an archaeologist in this Mummy, because it’s not about antiquity or knowledge in any way.

The women

And speaking of women, it is illustrative to look at the treatment of the main female characters in the 1932, 1999, and 2017 versions: Helen Grosvenor/Ankhesenamun, Evelyn Carnahan, and Jennifer Halsey and Ahmanet the Mummy, respectively.

The common theme of all the Mummy treatments hitherto is that said Mummy does bad things for the sake of love/lust, and as punishment was entombed alive. (Paging Dr. Freud…). So there’s a frisson of forbidden sexuality as well as religious transgression. The original (1932) movie returns repeatedly to the theme of sacrilege and trespass: inter alia, Imhotep’s use of necromancy to reanimate Ankhesenamun, the archaeologists’ entry into the tomb and violation of the curses binding the scroll of Thoth, even their unwrapping of the princess’ body:

Frank Whemple: Surely you read about the princess?

Helen Grosvenor: So you did that.

Frank: Yes. The fourteen steps down and the unbroken seals were thrilling. But when we came to handle all her clothes and her jewels and her toilet things – you know they buried everything with them that they used in life? – well, when we came to unwrap the girl herself…

Helen: How could you do that?

Frank: Had to! Science, you know…

All the layered tensions of cultural and sexual trespass in the 1932 Mummy center around and in the character of Helen Grosvenor: Being half-Egyptian, half-English and both herself and the reincarnation of Princess Ankhesenamun, she embodies the duality of the colonial. She is half ancient, half modern; half colonizer, half colonized; half alive, half dead; half the East, half the West. She is, effectively, Egypt itself. Not only her identity but her literal body is contested by these polarized forces, and her character is torn between them. She is, in a sense, the passive background against which the film frames its central questions: What are the costs of scientific progress? Of trespass? Does our pursuit of mastery over matter put us in danger from (non-material, non-Western) forces we can never understand? Helen is essential to the story in a way that, given the temporal and cultural context of the film, could only be portrayed through the perceived passivity of a gendered female body.

(The intersection of colonialism, archaeology, science, knowledge construction, gender, authority, place, and the supernatural make this film especially worth digging into, if you’ll pardon the pun.)

The 1999 version, though set in 1926, suffers no angst about colonialism. Bear in mind that the original was released only 9 years after the opening of Tutankhamun’s supposedly cursed tomb. But by 1999 we are sufficiently distant from those heady days that we don’t ask so many uncomfortable questions about trespass. Naturally it goes without saying that white people save the day, and that the hero is an American soldier–though more a soldier of fortune than a regular. This time the heroine is much more dynamic but–as reflected in her name, “Evie” (= Eve)–she is responsible for unleashing the ancient evil through her curiosity. It is made quite clear that the pursuit of forbidden knowledge–maybe just knowledge period–is dangerous. Whereas in the 1932 version the archaeologists give mini-sermons about the importance of “increasing the store of human knowledge about the past” and advancing science, in 1999 the motivation of the male characters is simply treasure, and that of the female character is scholarly acceptance and legitimacy. But although from a feminist perspective this is doubtless the best of the three films (the woman even saves the man’s life!), it seems like the writers couldn’t decide how to handle the erotic story component: They apparently felt it necessary to keep the damsel in distress element, but instead of making Evie and Ankhesenamun (read: Imhotep’s love interest) the same person, they split them so that there is no reason for Imhotep to be pursuing Evie (as opposed to some other hapless woman he could sacrifice). I’m not sure if it was felt that being in overtly sexual distress was too sexist or too creepy; or if they thought reincarnation was a bridge too far that the audience wouldn’t accept; or what.

Moving on to this year’s version, Jennifer Halsey is completely unnecessary to the story except as the life that Nick Morton must save to show us he’s not a totally Horrible Person. (He is a totally Horrible Person.) Otherwise she’s just there to translate a couple sentences of hieroglyphs and to be menaced by the Mummy. From this we see that:

(1) Colonial dynamics are back in a big way, just without any uncomfortable implicit self-criticism. The blonde, blue-eyed Caucasian beauty is threatened by the dangerous brown woman who just happens to be from an area now part of the “Middle East.” Coincidence? I think not. Somehow it even seems especially fitting that Halsey is British and must be rescued by an American soldier, like we’re replaying an America-centric narrative of WWII–here we come to save you from the baddies, Britain!

(2) Naturally our damsel in distress needs to be rescued by our paragon of American masculinity. She has no self-determination at all–she is ordered to Iraq by the male boss of the monster-hunting team, where her efforts are co-opted and derailed by her male companions’ looting; and for the rest of the movie one or the other of these men is calling the shots and she is left running along behind them.

Oh but wait, isn’t the Mummy in this movie female? Doesn’t that make it totally not sexist at all? By switching the Mummy’s gender, we’re supposed to spend the whole movie rooting for a (brown) woman to get her uppity ass kicked by (white) men. Note that the only female member of the monster-hunting team is the ineffective Halsey, who is also the only person who attempts (briefly, and of course ineffectively) to communicate with the Mummy.

The portrayal of Ahmanet the Mummy draws heavily on visual tropes from Japanese horror that are hella scary when done by the Japanese, but Hollywood’s attempts are always hamfisted. You know what I mean, the very white skin with the long wet black hair hanging over the face, writing on the body (in the Japanese context it would be protective Buddhist sutras), and the walking/crawling in a broken, disjointed manner. But Japanese horror isn’t just about the look, it’s the way it very skillfully turns your expectations of comfort back around on you. What you think is going to be a love story turns out to be literal torture, for example. It also excels in the application of very subtle touches to convey mood and build suspense. When it comes to horror, the Japanese get that women are mad as hell and given half the chance we might be unspeakably cruel and terrifying. Merely using the visual tropes without the underlying tension and mood comes off more like an uninspired pastiche. This Mummy is all image and no substance.

Indeed, the erotic component has now been almost entirely displaced from the story and characters onto the actresses’ bodies, in particular the scantily-clad Sofia Boutella as Ahmanet. To be fair both of the other movies also involve scantily-clad women; it’s just they also have plots. She needs to sacrifice Morton so that Set can inhabit his body (seriously, does nobody understand how gods are supposed to work anymore?) and then they will live happily ever after as king and queen of the damned or something. She ostensibly makes Morton her “chosen” because he freed her from captivity; we’re never given the sense that she is particularly taken with him sexually, albeit she tries to seduce him to her side; and he’s certainly not her eternal love from beyond the grave. Ahmanet’s entire motivation is power, not love or sex. But–not to beat a dead horse here–she is a McGuffin, not a plausible character.

The evil

In the 1932 Mummy, the evil–that is, what makes the Mummy a bad guy and a monster, as well as the plot device that consigns him to a living death–is necromancy. The implicit message is that life is for the living, death is for the dead, and never the twain should meet. If you raise the dead, then your punishment will be the inverse, to be entombed alive. Imhotep’s attempt at necromancy was a sacrilege against the gods, co-opting the magic by which Isis raised Osiris for use by and for mortals. Indeed the gods are a reality in this movie–it is Isis, not any of the humans, who ultimately puts an end to the Mummy.

Imhotep is a pretty obsessive dude, definitely a stalker by modern standards. He kills several people, and even worse, a dog, in his quest to get with Ankhesenamun. But basically he is lovelorn and just wants to be eternally undead with his princess, so it’s kind of hard to hate him.

1999’s Imhotep was having it on with the pharaoh’s concubine, and together they murdered the pharaoh, then Ankhesenamun kills herself. Imhotep is arrested but somehow gets free and does some necromancy. Of course he gets caught and you know the rest. Reanimated, he has two jobs: first, to kill those who opened his tomb, and second, to apparently be a terrible curse upon humanity. There are some obvious questions here–for one thing, if they went to so much trouble to punish Imhotep and keep him from rising from the dead, why did they subject him to a burial treatment where rising from the dead (let alone rising and then being an invincible one-man plague machine) was even a possibility? But I know, I’m applying too much logic here.

This version never makes it clear why necromancy is so bad (the gods never come into it), or why Imhotep is bent on world domination. He kills several people, which is bad, thankfully no dogs this time, but mostly he’s just another lovelorn obsessive.

The Mummy’s evil in the 2017 movie is, on the face of it, laughable: The bad girl kills the pharaoh and her baby brother. Big deal, that was just a regular Tuesday afternoon in the dynastic wranglings of ancient empires. Sure it was enough to get you executed and your name cartouches chiseled off your statues, but it certainly wouldn’t warrant being buried in a pool of mercury 1000 miles away from Egypt.

No, what apparently makes her really evilly evil is that Ahmanet performed some kind of witchcraft invoking Set, “the god of death” (I know, I know; if I rolled my eyes any harder they’d get stuck looking backward, but this is actually one of the least stupid things they say about ancient Egypt in this movie**), prior to patricide/fratricide. Throughout the film we’re reminded that Set is the god of death, and how terrible it is that Ahmanet wants to enable the god of death to be incarnate in a mortal body. One proposed solution: to allow Set to inhabit the mortal body and then to kill it and thereby kill the god of death! Again, clearly people do not understand how gods work.

So really what we are being told here is that death is evil. Could American death-denial possibly be writ any larger? I mean we’re not even talking damnation here, just plain old garden variety death. After Morton becomes possessed by Set, he uses his new superhero powers to reanimate two dead people. Indulge me as I unpack this a little more: In the previous incarnations of The Mummy, we are told that bringing the dead back to life is sacrilegious, blasphemous–the dead should be allowed to remain dead unless the gods decree otherwise. Now we are being told that necromancy is entirely cool because death is evil; anything that prevents death is thus good by definition. Nick Morton, for example, can be a Horrible Person, but he thwarts death three times, ergo he’s got a heart of gold even though he’s now using super powers to more efficiently loot antiquities.

In sum

What we learn from 2017’s Mummy is that death is evil, brown people are evil, women are either evil or useless, and all problems are solved by the application of US military force. Where 1932’s Mummy is full of the discomfort of a waning empire wrestling with the ramifications of colonialism, 2017’s is about taking everything from brown people that isn’t nailed down. It doesn’t even pretend that it’s for the good of the benighted savages, or that women are people. Its ethos is materialist and materialistic, exploitative and extractive, and most of all, in gibbering terror of mortality. Is this what American culture has come to? (Rhetorical question.)

*”Classic” for me generally means black and white and pre-1960s. But I also love Hammer films.

**They also overestimate the age of the New Kingdom by 2500 years.